Current Research:

|

My current research examines the nutritional ecology of various lemur species, and the effects of forest fragmentation and disturbance on the health and viability of lemur populations. My main study species, the diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema) lives in small, disturbed forest fragments at Tsinjoarivo. My teams have been monitoring sifaka study groups for 18 years - though some groups in fragments have gone extinct, others in moderately-disturbed fragments continue to survive and reproduce, suggesting that nutritional stress is not sufficient to cause starvation or disrupt reproduction. However, lower body condition in some fragments suggests a degree of nutritional stress, and mortality is higher in fragments, especially at the immature stage. My secondary study species, the brown lemur (Eulemur fulvus) is not found in any of the forest fragments, persisting only in the continuous forest. Combining research on these species, variable in both their ecology and tolerance to habitat change, can yield key insights into lemur adaptations, as well as informing conservation efforts. |

My primary current project is a comparison of the nutritional ecology of diademed sifakas (a folivore) and the frugivorous brown lemurs (Eulemur fulvus) at Ankadivory, a relatively intact forest site in Tsinjoarivo forest. The sifaka is highly frugivorous during the season of fruit abundance, but relies on leaves and flowers throughout the lean season, using hindgut fermentation to extract energy from these high-fiber foods. The brown lemur relies primarily of fruit year-round and uses a high throughput (short gut passage time) and cathermerality (feeding through the day and night). During 2016-17 my research teams collected detailed diet and food intake data as well as samples of foods. Analysis will quantify both nutritional intakes and seasonality, investigate which nutrients are limiting factors in each species' diet. Further, we will quantify the species intakes of PSMs (plant secondary metabolites - toxins and tannins) and the degree to which these impact food selection and limit food intakes in different seasons. This research is progressing in collaboration with Dr Jessica Rothman and Jean-Luc Raharison. |

Brown lemurs are mainly frugivorous - but consume some leaves |

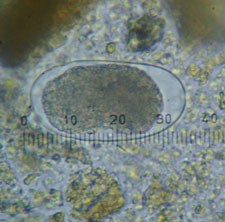

Parasite egg found in sifaka feces |

In addition to nutritional ecology, I am also examining the patterns of disease prevalence and parasitism (in collaboration with Jean-Luc Raharison, and doctoral student Laurie Spencer). This research will investigate the possibility that sifakas' susceptibility to nutritional or other habitat-related stress may increase in fragments, due to: (1) increased proximity to human settlement (i.e. forest edge) and increased potential for cross-species transmission, and (2) reduced body condition and compromised natural defenses. |

Finally, I am examining more direct indicators of physiologic health, derived from capture of lemur study groups over time (in collaboration with Jean-Luc Raharison, Dr Karen Samonds, Dr Laurie Godfrey, Dr Randy Junge, Dr Stacey Tecot and doctoral student Katie Heffernan). These data include morphometric data, dental wear, physiologic data from blood samples and fecal glucocorticoids as a measure of stress. This research will provide the most direct measures of health, which can be linked to dietary intake, and used to assess the utility of indirect predictors such as behavior and parasite load. |

Past Research:

1. Postdoctoral Research, conducted while at McGill University and Northern Illinois University.This research examined the nutritional consequences of dietary shifts which occur in sifakas in forest fragments. This began with intensive data collection across 2006-2007 focusing on four sifaka groups, and the concurrent collection of samples representing the most common sifaka foods. Following this, I combined chemical analysis of the foods with detailed analysis of feeding and intake rate data. This work has characterized the sifakas' diet in terms of energy intake, protein, fiber, sugars, fat and minerals, and thus quantified the nutritional consequences of seasonality, costs of dietary shifts observed in fragments. In short, sifakas appear to deal with reduced availability of fruit (the preferred food) in the lean season by eating less food, having lower nutritional intakes, traveling less, and conserving energy. Sifakas in disturbed fragments have reduced nutritional intakes relative to groups in more intact habitat - and the difference between sites is manifested in the rainy season only (lean seasons are equally lean in both habitats). This research was conducted in collaboration with Dr Colin Chapman, Dr Jessica Rothman, Dr David Raubenheimer and Jean-Luc Raharison. |

Diademed sifaka eating leaves |

2. 2001-2005: PhD Research, conducted while at Stony Brook University.

An adult male in group CONT2 |

In 2001, I supervised a regional census to examine the distribution of the nine lemur species at Tsinjoarivo in a network of 37 forest fragments varying in size, shape and isolation. This research showed that the primate species differ widely in their tolerance of fragmentation. Two species (Eulemur fulvus and E. rubriventer) were almost entirely absent from fragments. The sifaka (Propithecus diadema) is present in medium and large fragments, with a minimum tolerable fragment size of about 25 hectares. Other species can survive in smaller and more degraded fragments. During the behavioral study of Propithecus diadema in 2002-2003, I accumulated over 6,000 hours of behavioral data split among four social groups, of which two lived in continuous forest with minimal human disturbance and two lived in highly-disturbed and isolated forest fragments. |

|

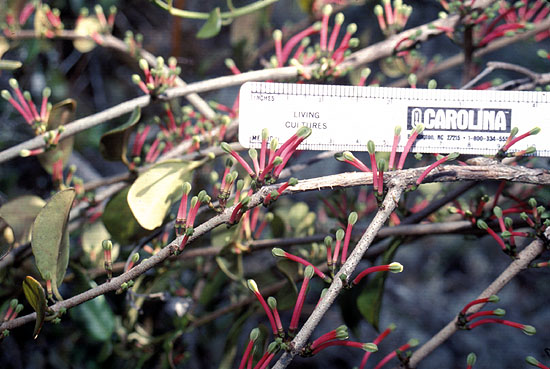

I found that the key to survival in fragments was a mistletoe – a small hemiparasitic plant found rooting in the canopies of host trees (for more information, visit the Parasitic Plant Connection website). Continuous forest groups use one mistletoe species (Bakerella clavata) as a keystone resource, meaning they rely heavily on it to get through the dry season, when the fruits they prefer to eat are unavailable. For fragment groups, choices are limited because the preferred fruit trees are absent (likely through a combination of natural mortality and human extraction). As a result, fragment groups have elevated the same mistletoe from keystone to “staple” resource, meaning it is the most important food item in almost all months of the year. This dietary shift has several consequences, including a drastic decrease in group cohesion (due to the small patch size of individual mistletoes, most individuals feed alone). The fitness consequences of the shift are hard to measure but several indirect lines of evidence suggest nutritional stress in the fragment populations (including a reduced body mass, especially for males – males are subordinate to females in this species, as in most lemurs). |

A mistletoe in flower |

|

For fragment groups, choices are limited because the preferred fruit trees are absent (likely through a combination of natural mortality and human extraction). As a result, fragment groups have elevated the same mistletoe from keystone to “staple” resource, meaning it is the most important food item in almost all months of the year. This dietary shift has several consequences, including a drastic decrease in group cohesion (due to the small patch size of individual mistletoes, most individuals feed alone). The fitness consequences of the shift are hard to measure but several indirect lines of evidence suggest nutritional stress in the fragment populations (including a reduced body mass, especially for males – males are subordinate to females in this species, as in most lemurs). |

During 2004, Jean-Luc Raharison and I collaborated on broader distribution surveys to better define the distribution of the Tsinjoarivo sifaka and contact more villages. In 2005, we started a reforestation initiative designed to reclaim fallow land and re-connect isolated forest fragments in the Mahatsinjo region. During this time, field teams led largely by Jean-Luc have continued to monitor the demography and behavior of the main sifaka study groups. The research team at Tsinjoarivo (myself, Jean-Luc Raharison, and the local research assistants) formed an organization in 2003, the Tsinjoarivo Forest Fragments Project (TFFP). |

The TFFP team in 2005 |

3. 1999-2000: Biological Surveys in Madagascar

Gilbert and Edmond collecting data (2003) |

In 1999, I co-led three survey expeditions in the remote rainforest corridor extending north from Ranomafana National Park. We discovered depressed population density in forests far from the park boundaries and increased prevalence of lemur hunting. In 2000, I led two survey expeditions. The first was a primate and bird census of Kalambatritra Special Reserve, an extremely remote rainforest isolate located in south-central Madagascar. This work resulted in the first characterization of the lemur community, and an expansion of the range of the endangered Madagascar Red Owl (Tyto soumagnei). The second survey was a primate inventory of Tsinjoarivo, where Ken Glander had just discovered the sifaka variant unique to that region. We contacted seven sifaka groups and clarified their distribution in intact forest and forest fragments. |